Art in a State of Siege: Insights into Political Turmoil

Art in a state of siege reflects the profound impact of political turmoil on creativity and expression, capturing the essence of human resilience amidst chaos. Artists such as Max Beckmann and Hieronymus Bosch have historically turned to their canvases in desperate times, using their work to confront and comment on societal unrest. Joseph Koerner’s exploration of these masterpieces in his book delves into how political unrest art not only reflects anxieties but also serves as an ominous sign for future generations. Art serves as a crucial conduit for grappling with fear and uncertainty, offering viewers a chance to project their emotions onto the canvas. In this way, art becomes a paradox, oscillating between beauty and despair, echoing the complex relationship between creativity and crisis in turbulent times.

In exploring creativity amidst crises, we find that artistic expressions during periods marked by upheaval often yield a wealth of insights about the human condition. The phrase “art in a state of siege” can also be understood as a commentary on the pressing challenges faced by artists as they navigate through oppressive environments and societal discord. Observing artworks like Max Beckmann’s compelling self-portrait or Bosch’s enigmatic triptych reveals how various creators respond to existential threats and project their hopes or fears onto the canvas. This examination of creativity under duress emphasizes the role of art as a reflective surface for personal and collective struggles, prompting viewers to engage with their own experiences through the lens of history. By rediscovering these iconic masterpieces, we uncover the ways in which art has historically served as both a document of societal tensions and a beacon of resilience.

Art as Omen: Understanding Historical Contexts

In turbulent political climates, art often emerges as a powerful reflection of societal anxieties and fears, acting as a prophetic omen for what is to come. Joseph Koerner’s examination of Hieronymus Bosch’s works reveals how art can serve as a tool for understanding past crises and navigating current ones. For example, Bosch’s triptych, “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” captures the chaos and moral ambiguity of its time, embodying the uncertainties that continue to resonate today. The ability of such artwork to transcend its historical context and connect with contemporary audiences speaks to its inherent power as a prophetic symbol.

Similarly, Max Beckmann’s “Self-Portrait in Tuxedo” serves as a lens through which one can analyze the ongoing struggles faced during periods of political unrest, providing insight into the emotional and psychological states of individuals caught in tumultuous situations. This self-portrait, created during the Weimar Republic’s decline, reflects Beckmann’s internal conflict and his response to the societal upheaval around him, presenting a narrative that invites viewers to find connections between their experiences and those depicted in the canvas. Such exploration highlights the role of art as both a record of societal turmoil and an omen for future actions.

Art in a State of Siege: A Reflection on Modern Turmoil

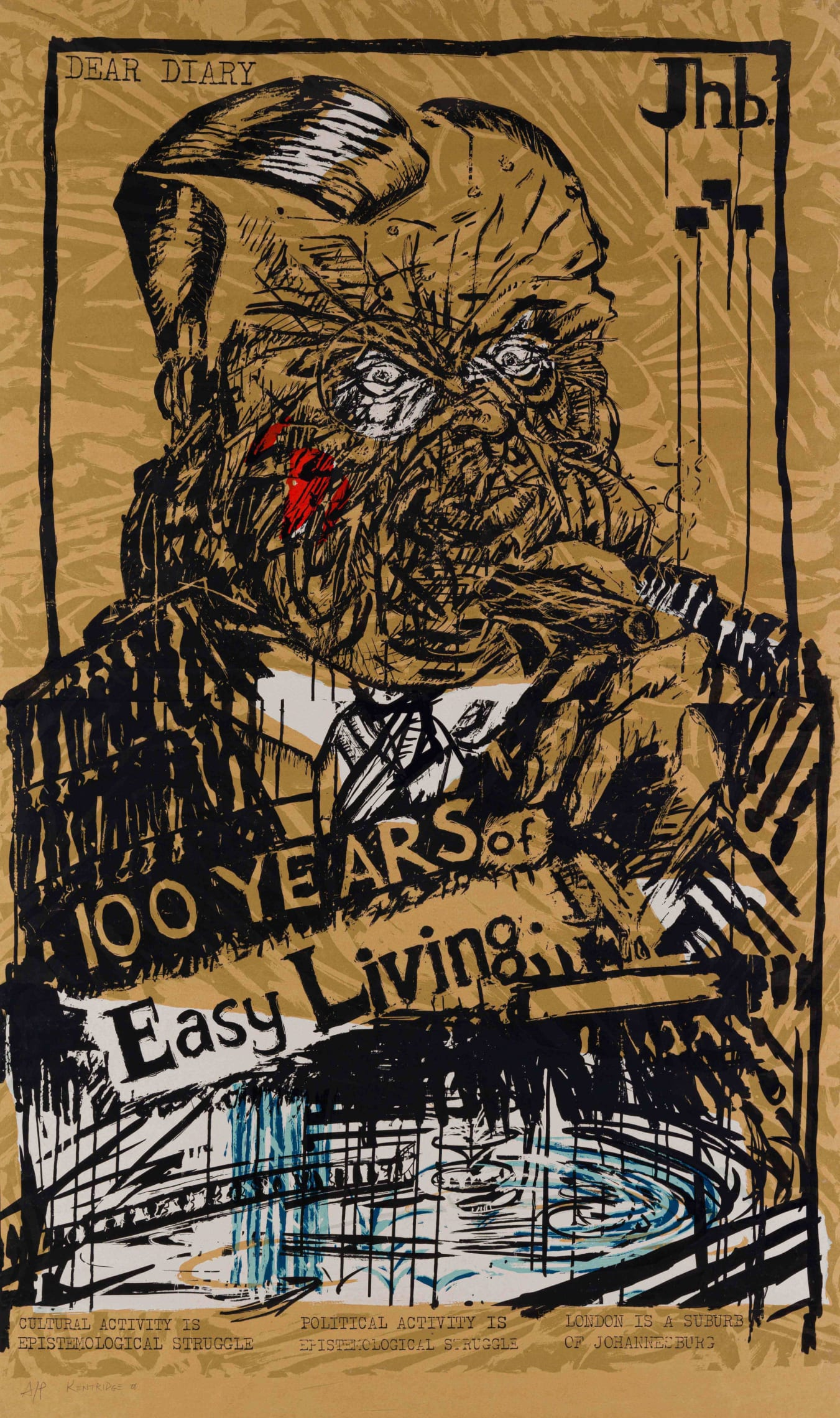

The phrase “art in a state of siege” captures the essence of how creativity persists amid crises. Drawing from Joseph Koerner’s insights, we learn that art reacts to the external pressures exerted by civil unrest, often serving not just as a commentary, but as a powerful, resonant voice amid chaos. Kentridge’s exploration of oppression and violence through his animated works underscores how artists use their craft to interpret and respond to the political environment, transforming their art into a form of resistance. This context allows for an understanding of how the societal condition essentially dictates the nature of artistic expression.

Moreover, this state of siege influences the viewer’s perception of art; much like Bosch’s presentations of moral and existential dilemmas, modern art becomes a conduit for processing contemporary issues. The relationship between art and its audience during periods of political unrest becomes a dance of interpretation, where the viewer’s own experiences can reshape their understanding of the artwork. Engaging with art during such times challenges society to bear witness to its own vulnerabilities and to question the narratives constructed by those in power, thereby transforming passive observation into a meaningful critique of ongoing injustices.

The Role of Artists during Political Unrest

Artists like Max Beckmann and Hieronymus Bosch had their creations deeply intertwined with the political realities of their time, functioning as barometers for the emotional and psychological climate of their respective societies. As Koerner highlights in his analysis, artists respond to the tumult of their environments, creating works that question and confront the brutalities of their era. In doing so, they not only provide viewers with a historical lens but also invite them to engage in the socio-political discourse that these artworks elicit.

The significance of studying artistic output during these chaotic periods reveals a deeper understanding of human resilience and creativity in the face of oppression. Beckmann’s self-portraits show the artist’s awareness of his roles as both creator and commentator, actively challenging the oppressive forces through his iterative exploration of self-identity. By studying such works, we uncover the necessity of art as a reactionary medium—one that both memorializes a moment of crisis and serves as a catalyst for both reflection and action.

The Intersection of Art and Political Narratives

Joseph Koerner’s reflections on art’s role during political unrest suggest that artworks often operate within and against the narratives defined by contemporary powers. This intersection is evident in Bosch’s striking imagery that layers rich symbolism and critique within its allegorical scenes, opposing the sanitized versions of morality preached by the rulers. In examining works like Bosch’s, we are compelled to confront the contradictions embedded in societal beliefs while recognizing that art itself can be a subversive act.

Moreover, Beckmann’s self-portrait encapsulates the struggle against authoritarianism, asserting the artist’s agency at a time when the very essence of artistic freedom was under siege. The dialogues between art and authority enrich our understanding of how artists navigate their roles during crises—utilizing their medium to not only depict narratives of suffering but also to envision a broader spectrum of human experiences that challenge dominant political ideologies. This forms a crucial part of art history that compels us to continually assess the societal functions of art in relation to its historical origins and potential futures.

Decoding the Ambiguities in Bosch’s Work

Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights” captivates audiences not merely for its fantastical imagery but for the uncertainties it provokes regarding heaven, hell, and human intention. These ambiguities evoke a sense of unease that resonates acutely within contexts of political unrest, encouraging viewers to project their own existential dilemmas onto the artwork. In doing so, Bosch creates a space for dialogue, allowing individuals to explore narratives surrounding sin, redemption, and the moral complexities of their own times.

As contemporary observers consider the chaotic elements woven into Bosch’s landscapes, it becomes evident that his work serves as a mirror reflecting anxieties about societal disintegration. The portrayal of various enemy archetypes—from moral decay to external threats—invites a probing analysis of how we confront perceived adversaries in our current landscape. In this way, Bosch’s triptych transforms into an enduring symbol, urging viewers to deconstruct their own realities and become active participants in their historical contexts.

The Emotional Weight of Historical Context in Art

Art serves as a poignant repository of emotions and experiences, particularly during periods marked by significant political anxiety. Koerner’s engagement with Beckmann’s work illustrates how specific contexts—such as the disintegration of democratic processes in post-war Germany—forge a unique emotional spectrum within an artwork. It not only conveys the artist’s response to their environment but also encapsulates the collective strife of a society grappling with its own identity.

By unpacking these emotional nuances, we begin to appreciate how artwork can evoke a sense of catharsis or confrontation. In moments of despair and uncertainty, such as those depicted in Beckmann’s self-portrait, viewers are invited to journey through complex emotional landscapes, mirroring their struggles against oppressive regimes. Thus, the value of studying such art is magnified, revealing deep connections between the past and present, and underscoring art’s potential as a powerful catalyst for social reflection and change.

Reflecting on the Impact of Art on Civil Discourse

In times of political turmoil, art possesses the extraordinary ability to influence civil discourse, creating platforms for dialogue around critical issues. Koerner’s study emphasizes that the artworks he examines, including Bosch and Beckmann’s, challenge social norms and provoke thought, urging society to confront its fears and align itself with narratives of resilience and resistance. These works become integral in shaping public perception and understanding of political events.

Furthermore, the conversation sparked by Koerner’s exploration reveals that, in the face of uncertainty, art can rally collective consciousness towards advocacy and social justice. By reflecting on the historical positioning of artists within their sociopolitical context, contemporary audiences can draw parallels to current struggles, creating a renewed awareness of how art can serve not just as a reflection of societal angst, but as a powerful instigator for change.

The Endurance of Artistic Expression Amidst Oppression

Art has an innate capacity to endure, even thrive, amidst systemic oppression. Koerner’s insights bring forth the idea that when conditions grow perilous, artists often find the urgency to create work that speaks to their realities. This resonates deeply with societies grappling with unrest, suggesting that art production can serve as both a form of defiance and a means of survival. For instance, Beckmann’s self-portrait not only asserts his identity and presence as an artist but also boldly challenges the political status quo of his time.

The durable nature of art crafted under duress highlights its role as a dialogue between the artist and the viewer, bridging historical events with personal experiences. As viewers engage with such works, they confront the historical narratives shaped by artists and reflect on their implications in today’s context. This capacity for art to inspire while simultaneously documenting strife allows it to maintain relevance, ensuring that the voices of the oppressed are never truly silenced.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does ‘art in a state of siege’ refer to in the context of political unrest?

‘Art in a state of siege’ refers to the role and perception of art during times of political turmoil and unrest, where artworks become symbols or omens reflecting societal anxieties. Joseph Koerner’s book explores this concept through various historical artworks, including Max Beckmann’s works created during the rise of fascism in Germany, illustrating how these pieces resonate with audiences facing contemporary crises.

How does Joseph Koerner connect Hieronymus Bosch’s art to modern political unrest?

Koerner connects Hieronymus Bosch’s art to modern political unrest by analyzing how his complex imagery reflects the fears and moral dilemmas of societies under siege. Bosch’s works, like ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’, are reinterpreted as omens, providing insight into our contemporary struggles, similar to how the anxious communities of his time sought meaning in his creations.

What insights does Koerner provide about Max Beckmann’s ‘Self-Portrait in Tuxedo’ in light of art during a state of siege?

Koerner highlights that Max Beckmann’s ‘Self-Portrait in Tuxedo’ captures the spirit of an artist grappling with political instability in post-WWI Germany. The painting serves as a metaphor for maintaining artistic integrity and responsibility amidst chaos, reflecting on how art can summon resilience in times of siege.

Why is art considered an omen according to Koerner’s ‘Art in a State of Siege’?

In ‘Art in a State of Siege’, art is considered an omen because it can foreshadow societal turmoil and moral decline. Koerner emphasizes that during political unrest, artworks resonate with viewers on a psychological level, prompting them to reflect on their circumstances and prompting action or introspection.

What are the key themes explored in Koerner’s examination of political unrest art?

Koerner’s examination of political unrest art explores themes such as the ambiguity of enemies within society, the psychological impact of conflict on artists, and the symbolic meanings of creations like Bosch’s and Beckmann’s works. He argues that art transcends mere aesthetic value, acting instead as a critical lens through which to view societal collapse.

How does ‘Art in a State of Siege’ contextualize the creation of art during crises?

‘Art in a State of Siege’ contextualizes the creation of art during crises as a response to the pressures of political instability, highlighting how artists integrate their societal experiences into their work. Koerner argues that artworks produced in such conditions often reflect an urgent need to process and communicate the chaos surrounding them.

What can modern artists learn from historical pieces studied in ‘Art in a State of Siege’?

Modern artists can learn from historical pieces studied in ‘Art in a State of Siege’ about the power of art as a response to societal challenges. By examining how past artists addressed conflict and uncertainty, contemporary creators can find inspiration to engage with their own political landscapes, using their art as a means of commentary or resistance.

How are viewers’ projections of their experiences reflected in Bosch’s art?

Viewers’ projections of their experiences are reflected in Bosch’s art through the ambiguity and complexity of his imagery. Koerner notes that during times of unrest, viewers often see their own fears mirrored in Bosch’s works, leading to varied interpretations based on personal and cultural contexts, making Bosch relevant in contemporary crises.

What significance does Koerner place on the representation of enemies in Bosch’s works?

Koerner places significant importance on the representation of enemies in Bosch’s works, suggesting that Bosch deliberately leaves it vague to provoke thought. His art portrays a range of potential foes—be they moral, cultural, or political—highlighting the multifaceted nature of societal threats and the human tendency to see others as adversaries in times of strife.

| Key Points | Details |

|---|---|

| Art in Time of Crisis | Joseph Koerner examines how art reflects societal fears during troubled times, using historical works as lenses for understanding present political unrest. |

| Main Works Discussed | Koerner’s book highlights Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” Beckmann’s “Self-Portrait in Tuxedo,” and Kentridge’s animated drawing, analyzing their significance in different political contexts. |

| Concept of a “State of Siege” | Coined by Kentridge, it denotes a situation where civil rights are restricted under the guise of maintaining order, explored in modern contexts through the lens of art. |

| Ambiguity in Bosch’s Art | Bosch’s works, particularly the triptych, leave the interpretation of enemies unclear, amplifying societal fears and the perception of chaos in turbulent times. |

| Personal Connections to Art | Koerner’s interest is partly rooted in his father’s experiences as a Holocaust artist, reflecting how personal histories inform the understanding of art amidst trauma. |

| Contemporary Relevance | The study of art during political upheaval provides insight into how societies interpret existential threats, emphasizing art’s role beyond mere aesthetics. |

Summary

Art in a state of siege captures the unsettling interplay between creativity and conflict. In turbulent times, artists and their work resonate deeply with societal anxieties, serving as both reflections of chaos and guides for navigating uncertainty. Joseph Koerner’s latest exploration underscores how historic artworks emerge as powerful omens, revealing the ways in which art transcends its traditional boundaries to comment on pressing contemporary issues. By examining pieces from Bosch to Beckmann, Koerner illustrates that art is not just a passive observer but an active participant in political discourse, pushing audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about their time.